When the Glenstone museum debuted a big expansion in 2018, its inaugural installation included a pointed pairing of two paintings that use the American flag as a motif. Next to one of Jasper Johns’s signature flag canvases, Flag on an Orange Field II (1958), was Faith Ringgold’s Black Light Series #10: Flag for the Moon (1969). In Ringgold’s treatment of the subject, text spelling out a racial slur is camouflaged within the stars and stripes—the artist’s way of juxtaposing the celebration of America’s space triumph of that year with events occurring on the ground.

As Glenstone’s curatorial associate Fanna Gebreyesus, recalls, “It was not the kind of chronological hanging you see all the time. Johns and Ringgold were working around the same time, and she was also influenced by Pop Art and Minimalism. But having a Black woman in that space, it takes it to a completely different level.”

Now Glenstone has reopened its galleries for the first time since the pandemic with a thorough survey of Ringgold, who at 90 is receiving new recognition from museums in the U.S. and abroad. Glenstone, which owns nine works by the artist, is the only American venue for “Faith Ringgold,” which was initially organized by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Melissa Blanchflower for the Serpentine Galleries in London in the summer of 2019 and then toured to the Bildmuseet in Umeå, Sweden last fall.

The show (which runs through October 24) is the first traveling exhibition to be held at Glenstone, which has previously only showcased art in the museum's collection. In other ways, too, “Faith Ringgold” seems to represent an evolution of the Glenstone model. According to its mission statement, the museum, founded by collectors Mitchell and Emily Wei Rales and located on a sprawling 300-acre campus in the D.C. suburb of Potomac, Maryland, “seamlessly integrates art, architecture, and nature into a serene and contemplative environment.” Ringgold’s work may be said to pull viewers out of that environment, presenting detailed images and clearly narrated accounts of racism, sexism, and other kinds of oppression. Even a single painting of hers can send shock waves through a collection, as in the Museum of Modern Art gallery that places her painting of a bloody riot—Die (1967), from her “American People” series—in proximity to Picasso’s Desmoiselles D’Avignon.

Installed mainly in chronological order, the exhibition (organized for this venue by Emily Wei Rales) attests to a long career of intertwined art-making and activism. It begins with works from “American People” and other series of the 1960s, including Ringgold’s “Black Light” group of paintings exploring the rendering of dark skin tones in a restricted but richly nuanced palette of black, brown, and umber; as Gebreyesus points out, Ringgold was putting her own twist on Ad Reinhardt’s contemporaneous all-black abstractions.

Around the same time she was making political posters, aligned with the Black Power movement and other causes; several examples are also on view, including one she made for “The People’s Flag Show” at the Judson Memorial Church in 1970. Ringgold had co-organized the exhibition with two other artists as a protest against laws prohibiting the desecration of the American flag, which had been used to arrest and convict an art dealer; Ringgold and her fellow curators were also arrested a few days after the Judson opening. (The charges were ultimately dropped).

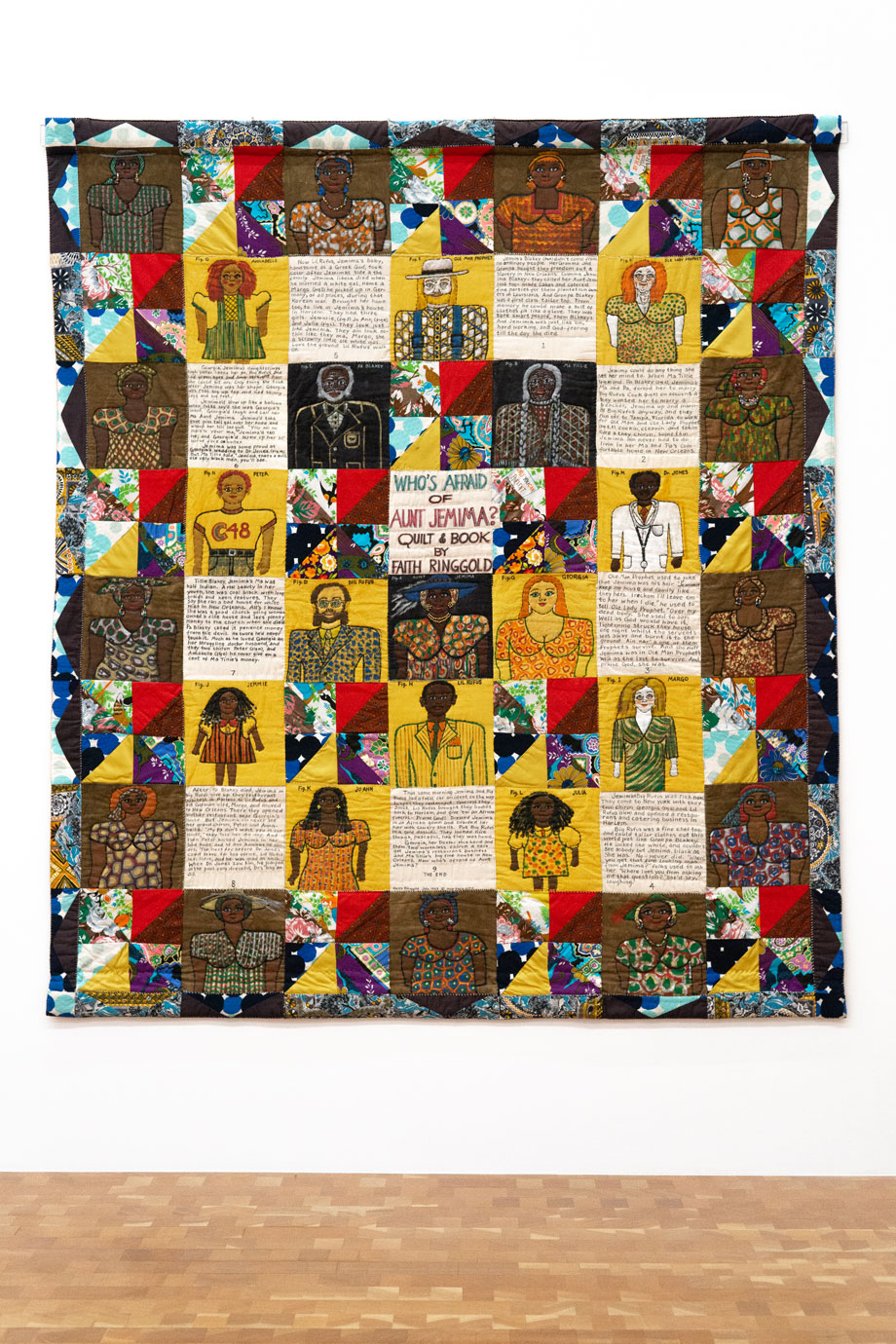

Later galleries follow Ringgold’s forays into quilt-making and soft sculpture, with clusters of black-fabric figures that date from the 1970s and numerous examples of the “Story Quilts” she started to make in the 1980s. In these richly detailed painted and pieced textiles, Ringgold explores multiple forms of storytelling: visual, in the detailed portraits and street scenes on the quilts, and textual, in the long narratives written directly on them. Some of her stories are autobiographical, as in the Tar Beach quilts that reflect on Ringgold’s childhood memories of viewing the George Washington Bridge from a rooftop in Harlem, while others, like Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?, confront racial and gendered stereotypes.

Ringgold’s direct and unflinching engagement with American history and politics, which was explored from a distance in the European exhibitions, may come across with particular intensity at Glenstone (which sits just 25 miles or so from Washington, D.C.). Gebreyesus notes “the geographic weightiness of our proximity to the capital of the United States, especially when you think about some of these more overt political works such as The Flag is Bleeding.”

Also significant is the timing of this stop on the exhibition tour. “It was such a profound experience opening in 2021,” says Gebreyesus. The pandemic year and its revelations about structural inequality in American life, she explains, added resonance to Ringgold’s already powerful work: “It just hit everyone so much harder than it did when we first started working on the show.”

In a video on Glenstone’s website that was produced for the exhibition, Ringgold talks about the making of her 1997 painting The Flag is Bleeding #2 (American Collection #6), which is in Glenstone’s collection. “It is very difficult to paint blood because you feel like you’re bleeding,” she says. “The flag was bleeding and still may be.”